“ More than anything else, I find stimulation in the materialization of an unpredictable expression. The biggest meaning of this phenomenon might just be Zen. ” — Shozo Shimamoto

For a long time I have been studying the work of Shozo Shimamoto, initiated first by my longtime friend, collector and art producer Diego Strazzer. I could work in the best conditions thanks to the remarkable archives of the Shozo Shimamoto Association in Naples, Italy, where Teresa and Guiseppe Morra conserve with an aesthetic passion and a scientific rigor so many treasures of works and documents to understand and appreciate at its right level the importance of Shozo Shimamotos’ legacy. From Arman to Cai Guo-Qiang, and passing through Miro, I have been always fascinated by artists facing the complex and metaphysical problematic of the destructive creation – a terminology I proposed in my book Cai Guo Qiang and Pompei: inside the Volcano . No doubt that destructive creation has been a leading process in the development of the visual arts in the second part of XXth Century. In Europe, we immediately think of artists like Alberto Burri who made works by burning wood panels, or Lucio Fontana lacerating his canvases; or Miro burning in part its last paintings of the 1970’s. The Centre Pompidous’ chief curator Catherine Grenier, in an academic essay for her exhibition held at the French National modern art museum in 2005, Big Bang: Destruction and Creation in 20th Century Art, was even saying that the “common denominator of the work of twentieth-century artists as well as our contemporaries, is [...] a paradoxical impulse that closely links two terms: destruction and creation.” From my point of view, we can think of many reasons for this “paradoxical impulse“. There is at first an aesthetical and classic approach which comes from much earlier than our times: XVIIIth Century French philosopher and art critic Diderot had explained already for instance how destruction could be creative, going against the common idea that creation and destruction were antithetical. In the legendary essays of his Salons, Diderot imagines the sculpted group of Pygmalion by Falconet to be even more perfect if it had been destroyed in places... Later, in the poetry of the end of XIXth Century marking the beginning of the Modern era, Arthur Rimbaud wonders in his Illuminations: “Can we rave about destruction?” A certain destruction of the (ancient) world is in Rimbaud's poetry the necessary prelude to the advent of a new life: “Death whistles and circles of dull music make this adored body rise, widen and tremble like a specter; scarlet and black wounds burst in their superb flesh. The clean colors of life darken, dance, and emerge around the vision, on this chaotic site…”: In his Illuminations, Rimbaud wants poetry - which is to say art- to transform life. There, creation can only be true after destruction. How come a disaster can become a source of artistic creation? A very significant motivation of the destructive processes in the art of the mid XXth Century has been certainly the desire of the modern artists to get rid of the ancient world, meaning to free themselves from the sacred rules of academic art, and the duty to create “beautiful” works. Let us remember the explicit goal of Miro who said early in his career he wanted “to murder painting,” that is to say, to free his art from academicism and from rules. Or Picasso repeating : “Beauty I do not care of”. Last but not least, there is also perhaps the influence of the World War II horrors and destructions taking a part in this process: how could the artists propose to raise a form of creation – and so a meaning of life- out of a destroyed world? The brilliant retrospective of Alberto Burri at the Guggenheim New York in 2015, purposely entitled “The Trauma of painting”, started by the screening of archival images of the Italian cities in 1945, totally destroyed. The show wanted to focus explicitly on how “Burri’s work both demolished and reconfigured the Western pictorial tradition, while reconceptualizing modernist collage” - as the Museum said in its introduction. As a matter of fact, through his inventions in art, Burri built a new world, a new art, within this tragic context of a ruined country. Arman grew up also during the war, and it is a fact that a very important dimension of his work is based on a destructive creation process. In performances he called “rages”, Arman destroyed, broke, burnt furnitures and objects, to “use his energy in destruction,” creating new elements born of this operation of transformative destruction. He gathered the debris of his destruction on a canvas, making a composition similar to the photograph of an explosion, which became the work of art, as with Chopin's Waterloo, a panel created from the destruction of a piano during a performance in March 1962. At the same period of history, most probably without knowing those Europeans experiments and the artists mentioned, in a Japan destroyed by the war and two atomic bombs, Shozo Shimamoto developed his “Holes” series, burning and lacerating drawings. He will then create a new form of art through “atomic” performances where he will crash and explode bottles of colored painting on canvases. In one of his first art actions, during the 1956 outdoors Gutai exhibition on the banks of the Ashiya River, Shimamoto involved the use of a cannon to shoot glass bottles full of paint at a large sheet of canvas suspended from a tree. During all his career, Shozo Shimamoto has explored and pushed the boundaries of painting, by exploding his multicolored bottles onto canvasses, by crashing layers of thick matter on them, and by perforating the paper canvas, giving way to his Ana (Holes) series. Shimamoto conceived his painting as a hole, by breaking through layers of glued newspaper.

With Shozo Shimamoto, art is born again in a performance symbolizing the violence and the destruction. Art demonstrates again how a form of life and beauty can arise from the chaos. An Anthropologist approach would say there is perhaps a form of catharsis in this artistic process. There is no doubt that for the artists of the post-world war II, the duty of art was to search a new meaning for life, and to participate to propose a new world built on the ashes of the ancient one. When the Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai (Gutai Art Association) later known as “Gutai group” is founded in 1954, it marks the need for the post-war Japanese artists to reset radically the art scene. Along with Painter Jiro Yoshihara, Shozo Shimamoto is among the founders of the group and is the one who eventually proposes the term gutai, which means both in Japanese “concrete” and “embodiment” – a way to mean the importance of the art process, of the concrete action and the body of the artist to value and understand properly the artwork. The artists who were part of the Gutai movement shared the same interest and priority in the art-making process itself rather than the finished work. The group of young artists want to develop a radical rethinking of the Japanese artistic tradition, having as reference the informal practices but also forcing them in a direction of cancellation and annihilation. The response of the audience is then difficult: as Shimamoto recalled, ‘the time was disastrous for us because it was right after the War and we had been defeated. So people didn’t want to see destruction and violence, and they didn’t want to accept what they had done. So what we did was completely neglected by the audience.’ The group thus enters into relation with the western avant-gardes, and in many cases turns to be a precursor of many experiences carried out by European and American artists years later. The case of Shozo Shimamoto is emblematic from this point of view, because he is among the first, in the fifties, to “betray” the painting in the name of something else, in the name of a pictorial event. Far before the trend of the “performing visual arts”, becoming important in the 1960’s-70’s, with for instance the Fluxus movement, Shozo Shimamoto invents in a sense a new form of making art, and a new vision of what could be an artwork. As he said: “The act of painting is to suggest free expression. This is the true work of an artist”. If art historians are recognizing more and more the importance of Shimamoto’s contribution to the art of XXth Century, he still need to be diffused and studied as a leader who has generated a huge and capital legacy until today. Many artists are following today the modernist aesthetics of the destructive creation as well as the “performing paintings” initiated by Shimamoto. The major figure is obviously Cai Guo-Qiang, whose last exhibition in Italy at the MANN I curated. Through his gunpowder signature painting, Cai Guo-Qiang throws fire on the canons of a conceptual contemporary art that has become traditional and academic, and renews in this sense with the experimentation as the greatest challenge of art. A process that involves working on the creation of forms, starting with their destruction.

The present presentation of a survey of works by Shozo Shimamoto at ALIEN Art Centre, Kaoshiung, is carried out with the cooperation of the Shozo Shimamoto Association & the Morra Foundation, Naples, Italy, which features in its collection the largest collection of the works by the Japanese artist worldwide. This exhibition represents the first survey of Shimamoto ever presented in Taiwan, a country very marked by intense and historical cultural inter-exchanges with Japan. Our show consists in three different types of works, to give to see the evolution and the process of Shimamoto art from the early 1960s until the last part of his life where he achieved his most spectacular performances in Italy organized by the Morra Foundation, one of the very first pioneer art center dedicated to the performing visual arts. As a memory of Shimamoto’s early practice the show includes a selection of “holes”. The “holes”, works formed by the overlapping of sheets of paper, covered mostly by a layer of dirty white material, on which the artist acted, rubbing over it to produce lacerations that left open like substantial breaks and gaps on the surface. Holes is one of a series of works which Shimamoto begun either in 1949-1950 in his studio in Nishinomiya City. Meaning before Lucio Fontana started his holes paintings in 1954 as a way to restore the picture plane to three dimensions or a space, which will make him so famous. Shimamoto’s Holes are works in which the intention to go beyond the form, to treat the surface as a physical fact and to think of the pictorial act as an event is evident. The “holes” are overcome and Shimamoto moves on as if he extracted, from that technique and the logic connected to it, the importance of the action beyond the material piece, the size of an event, which to some extent is absolutized, in the sense that it is detached from a final outcome, other than the event itself. The core of the project reflects this crucial passage and involves the will to overcome a logistic necessity of cutting the very large canvases – used by Shimamoto in many of his Bottle Crash performances – into smaller pieces, more manageable and easier to stretch on canvas in subsequent moments. This is an attempt, for this special presentation, to bring back the oeuvre as it was initially thought; to get back together the multiple scattered pieces of an enormous black and white canvas, and give to the spectator a suggestion of resemblance to the original magnitude and scale of Shozo Shimamoto’s endeavour. A rare selection of paintings are presented here, starting by the beautiful and fairly less knowned Nyotaku series, and followed by the most famous series of monochroms and bottle crash paintings, coming from the legendary public performances of the Gutai leader. Finally will be presented a work on film which is an extraordinary experience of anticipation of the American avant-gardes. This seven minutes experiments sees Shimamoto, already during the Fifties, acting manually on the film, adding color to the photograms and even manipulating them until partial breakage. These features make this a very special piece as it is a powerful precursor of western experimental film masters who started manual film modifications several years later. We also present the screening of a live performance by Shozo Shimamoto made in Italy, where one can see the making off of the legendary “Bottle crashed paintings” series. His 2008 performance at the Ducale Palace of Genova is entitled: “Samurai acribata dello sguardo”, meaning the “Samurai acrobat of the gaze”… The samurai of the colors is indeed in full action. To give us to see and to think of the essence of the artistic gesture: a celebration of freedom. In a famous text entitled You Have to Paint badly, Shimamoto asserts: « Setting the condition that people paint badly is essential if they are to feel at ease, and this is the most important thing in painting, because it brings us back to its point of origin, which is the joy of painting, and not a test of technique.” In this purposely provocative manifesto (“Art is something that shocks people”, the artist used to say), Shimamoto wants to demonstrate that a new form of art can’t come out of the restrictive and limited rules of virtuosity and academism. On the contrary, “by continuing to paint badly (the artist meaning by painting out of the norms and rules of academism), it is really possible to create an ugly, personal, and unique style. This is how the most interesting new art comes into being, and it is here that creation begins. ». Our exhibition aims to show through a selection of works by Shimamoto, how a new style could emerge from this aesthetical statement. A vanguard style which inspired after so many contemporary artists around the world. Let us remind that the work of Shimamoto has been widely exhibited internationally. Shimamoto was invited to participate officially in the 1993, 1999 and 2003 Venice Biennales of contemporary art, the leading reference festival of art. In the 1998 touring exhibition “Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949–1979” organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, his paintings hung alongside works by works by Lucio Fontana and Jackson Pollock. In 2014, the Guggenheim New York presented some works in the historical show “Gutai: Splendid Playground”. Recently, a beautiful retrospective curated by famous Italian art historian Aquile Bonito Oliva was presented in Palermo, in 2018, in the framework of the cutting edge Manifesta art festival. Like most of the artists of the post-world war II generation, Shozo Shimamoto has been always a peace activist. One of his performance paintings was entitled Heiwa no Akashi (“A Proof of Peace”) (2000), in which he dropped bottles of paint on a concrete canvas while lifted in midair, is installed as a monument at Nishinomiya Yacht Harbor. The work is supposed to be continued every year for 100 years on the condition that peace remains in Japan. This is just the beginning of the story. Long life to the Samuraï of the colors!

WHIRLPOOL, 1967, 93x118 cm. Private collection

Punta Campanella 46 2008, 189x202 cm. Private collection

Capri 36, 2008, 202x213 cm. Private collection

Magi, 2008, 159x228 cm. Private collection

Magi S, 2008, 150x200cm. Private collection

Shozo Shimamoto Palazzo Ducale Genova 2008 © A. Mardegan

Genova 23, 2008, 170x194,5cm. Private collection

Genova 36, 2008, 187x247cm. Private collection

Reggio Emilia, 2011, 167x200cm. Private collection

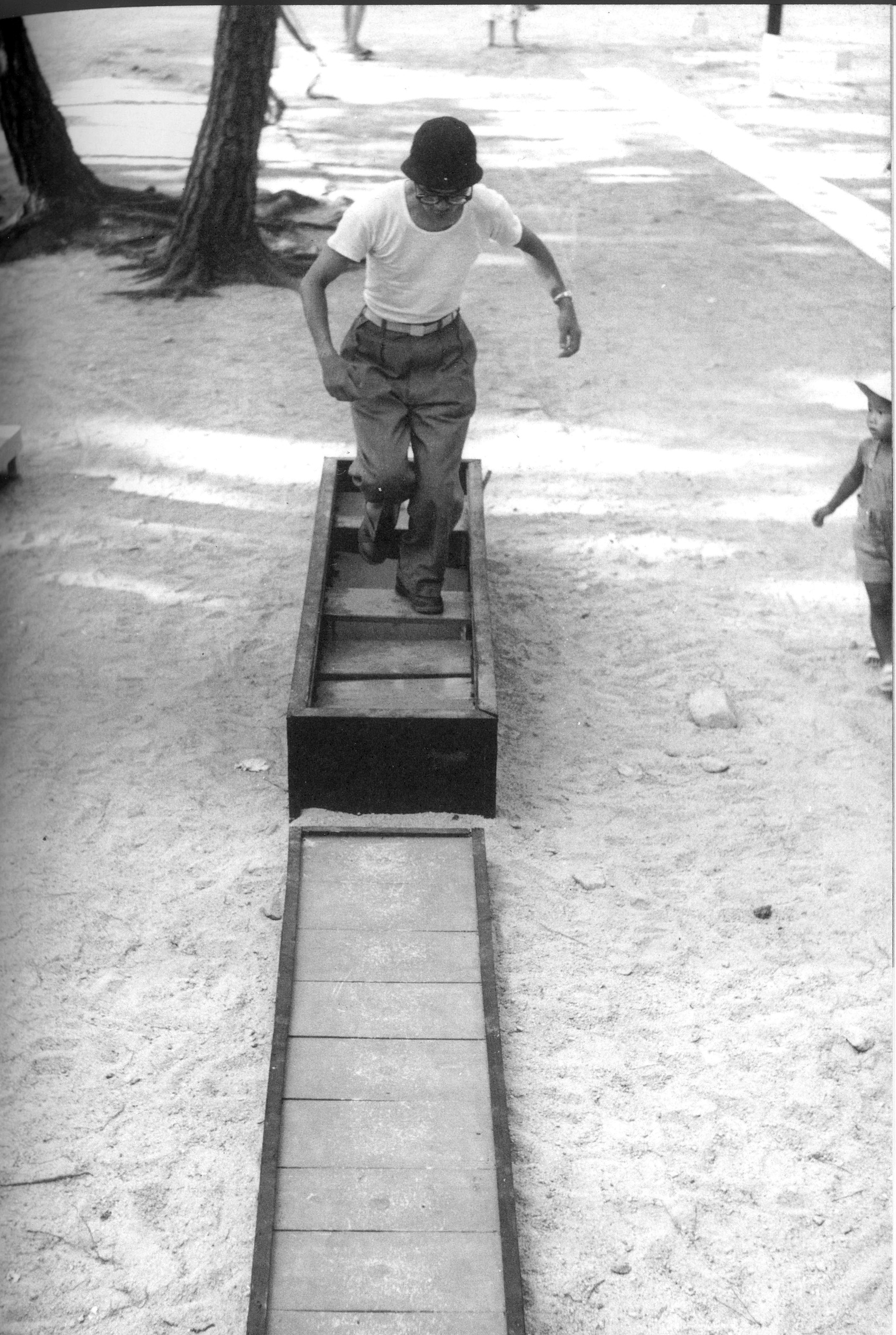

Kono ue o aruite kudasai (Please walk on Top, painted wood, installation view The Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition 1956© Associazione Shozo Shimamoto

Painting with glass bottles of paint, the 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition , Ohara Hall Tokyo October 1956 © Associazione Shozo Shimamoto

II gutai Exibition Hurling colors 1956 © Associazione Shozo Shimamoto

Shozo Shimamoto Un'arma per la Pace piazza Dante Napoli 2006 foto di Fabio Donato ©Fondazione Morra

WHIRLPOOL, 1967, 93x118 cm. Private collection

Punta Campanella 46 2008, 189x202 cm. Private collection

Capri 36, 2008, 202x213 cm. Private collection

Magi, 2008, 159x228 cm. Private collection

Magi S, 2008, 150x200cm. Private collection

Shozo Shimamoto Palazzo Ducale Genova 2008 © A. Mardegan

Genova 23, 2008, 170x194,5cm. Private collection

Genova 36, 2008, 187x247cm. Private collection

Reggio Emilia, 2011, 167x200cm. Private collection

Kono ue o aruite kudasai (Please walk on Top, painted wood, installation view The Outdoor Gutai Art Exhibition 1956© Associazione Shozo Shimamoto

Painting with glass bottles of paint, the 2nd Gutai Art Exhibition , Ohara Hall Tokyo October 1956 © Associazione Shozo Shimamoto

II gutai Exibition Hurling colors 1956 © Associazione Shozo Shimamoto

Shozo Shimamoto Un'arma per la Pace piazza Dante Napoli 2006 foto di Fabio Donato ©Fondazione Morra