Text / Robert C. Morgan (the co-curator of In Silence and a American art historian)

From my Western perspective, I understand Hong-wen’s work as being possessed by a heightened degree of sensory cognition that suggests a process of seeing in relation to knowing. Seeing into knowing suggests that my experience with the artist’s work is directly related to my sensory (visual) input that occurs prior to language. To fully understand this approach to Hong-wen’s art, I have to go beyond language, beyond the display of rote information. I want to see Hong-wen’s massive painterly diptychs and upright welded sculpture taken beyond the talk of economic status and into the realm of our sensory functions, the experiential domain of art. What we see and how we feel in relation to the act of seeing may be related to one another, but are not precisely the same. This has proven evident on several occasions where Hong-wen has shown in exhibitions, including New York, Poland, East Asia, and Europe. The works to which I now refer are mostly his paintings and sculptures -- the focus of the current exhibition.This is not to exclude the importance of his work in other mediums, namely video, prints, drawings, and his amazing large-scale installations involving intensely creative multimedia forms.

For several years, I have observed paintings and sculptures by Lin Hong-wen that suggested a Zen absence of form in addition to a precise metaphysical reality. In China, metaphysics is largely contingent on the teachings of Confucius. From a Western point of view, the leading advocate would be Aristotle. As far apart as they may seem, the two philosophers share the notion that metaphysics exists both within and beyond what we can identify as being in the physical world. One might further argue that the stoic Zen aspect in Hong-wen’s work shares a similar sense of being in-between, but from a slightly different perspective. There is little doubt that the artist’s acute abstract sensibility is both absent and present. What it becomes –in time –is what it is, and, therefore, suggests Hong-wen’s manner of work exceeds the normative approach to Western contemporary art, whatever that approach has come to mean in the twenty-first century.

Metaphorically, the artist delivers a sensorial affirmation that clarifies the stillness that resides within his art, a stillness of what it may likely become within the silent coordinates of space/time. Having knowledge of this, I am willing to experience Hong-wen’s work for what it is – not only as a material, but coincidentally as form within structure. In so doing, I am able to relate to Hong-wen’s work by avoiding any need to conform to outsider opinions expressed through media, which are most often incorrect.

Rather I come to his work on terms of my own, alleviating any presumptuous academic or commercial language. I understand his work as an instrumental force, an exuberance that goes beyond institutions and, in its own way, has chosen to perceive the role of art as a rejuvenating phenomenon that gravitates toward personal experience. This relates directly to the manner in which the artist’s emotional, often dynamic intelligence informs his work and the manner in which it perpetually revises assumptions regarding past histories. Through his manner of dealing with both Eastern and Western art, he has discovered new ways to augment his personal working methods.

An independently focused artist, Lin Hong-wen does not make art for any purpose other than the pursuit of a creative impulse. He is an artist of his time. In focusing on his materials, whether acrylic or steel, he enhances the driving force behind his untimely intuitions, thereby refusing to calculate or subscribe to methods resulting in solely rational conclusions. His approach to art is neither systematic nor predetermined. Rather he is involved in the ongoing discovery of form in which he avoids any common or predictable aspects of entitlement. Consequently, his work remains open and without limitations. His allegiance to form is not formal, at least not in the traditional sense. Hong-wen works outside the realm of the obvious, removed from trends that speculate on a global art market. As a uniquely cultivated artist, he avoids engaging in projects he foresees as problematic or unsuitable for his purposes. His inspiration emanates from a singular point of view. This is what enables him to focus entirely on his work. He is an artist of his own making.

To perfect the idea of painting and sculpture toward the physicality of a work of art is a persistent goal for any serious artist. It does not happen all at once. Nothing happens all at once. It takes time. To arrive at “emptiness” (wu-nien) from an Eastern point of view is a matter of letting down the barriers. In doing so, the artist allows the work to become itself. There are moments when a painting congeals through the addition of multiple layers of paint that transform the painting in a way that appears as if one painting was painted over another. This enables the work to find its own resolution. At other times, a second canvas may be placed adjacent to a previously painted one so as to extend the painterly surface toward wider dimensions and thus to create a sense of openness without giving the surface an appearance of opposition.

While in Western terms this would be called a diptych, this is not accurate from the point of view of the Lin Hong-wen. Rather, the second canvas is removed from its isolation in order to give priority to the first. New visual elements enter into the perceptual field in a way that allows the initial surface to become transformed into a larger space, an immeasurable space, which may constitute a feeling of emptiness. Put another way, the two surfaces ultimately become one.

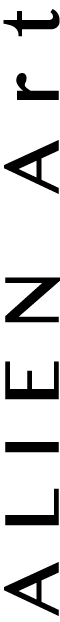

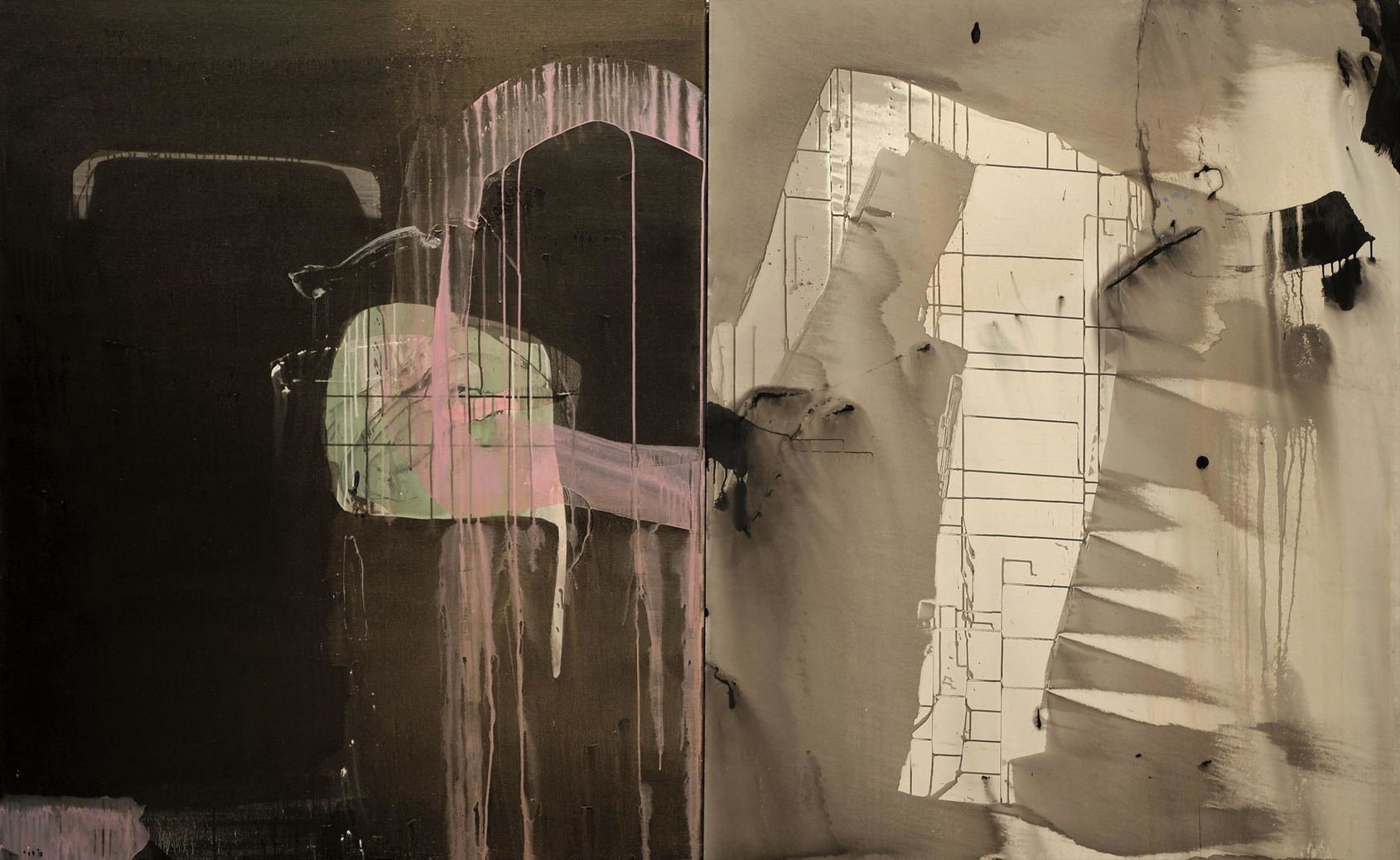

Lin Hong-Wen, Untitled 3, 2019, acrylic color, canvas, 260 x 162 cm We see this process happening over and again in paintings such as Untitled 3 (2019) where the ambiguity and architectonic separation of color and gesture form a complexity whereby the thin layers of paint begin to resemble ink. What might appear at the outset as oppositional emerge instead as a holistic unity, a sense of oneness. This is truly the Chinese way in which the impulse of the Tao (The Way) is discreetly tempered through the diurnal Analects of Confucius. Here the force of nature is given what may appear as an abandoned aesthetic repository as in Untitled 7 (2019) whereby the metaphysical reality on the two-paneled surface reveals a black and white rectangle co-habiting with a Sienese polygon similar to the earth colors used in the Italian Renaissance.

Lin Hong-Wen, Untitled 7, 2019, acrylic color, canvas, 144 x 91 cm In the paintings of Lin Hong-wen this is precisely what happens: The energy (qi) of the Tao is given over to a metaphysical current of unpredictable clarity. The paintings become what they are, rather than a simulation of something else. They conjure a sense of emptiness, synonymous with the Tao. Human perception belongs to Nature as we discover form that takes us beyond any previously known dimensionality we may have struggled to retain. Beauty can be defined in these terms but only if we allow our connection to Hong-wen’s paintings to exist experientially and openly on their own, rather than depending on scholarly encounters from the past.

In contrast to the position of Modernist abstract painting in Europe and New York, Chinese (Taoist/Confucian) metaphysical painting holds remarkable differences. This is not to suggest that these differing approaches to abstraction are not assessable. In fact, it is quite the opposite. I would prefer to understand the ambient relatedness between the two hemispheres as being complementary rather than polarized. By this, I refer to what has been left out of Modernist abstraction in the West, namely a more subtle, deeply philosophical approach to painting in contrast to theory. Within the paintings of Lin Hong-wen, we discover a more readily available opportunity for Westerners to awaken their minds to the ultimately receptive aspects of painting that offer a sense of well-being in a world increasingly bent on dissention, fragmentation, and poverty.

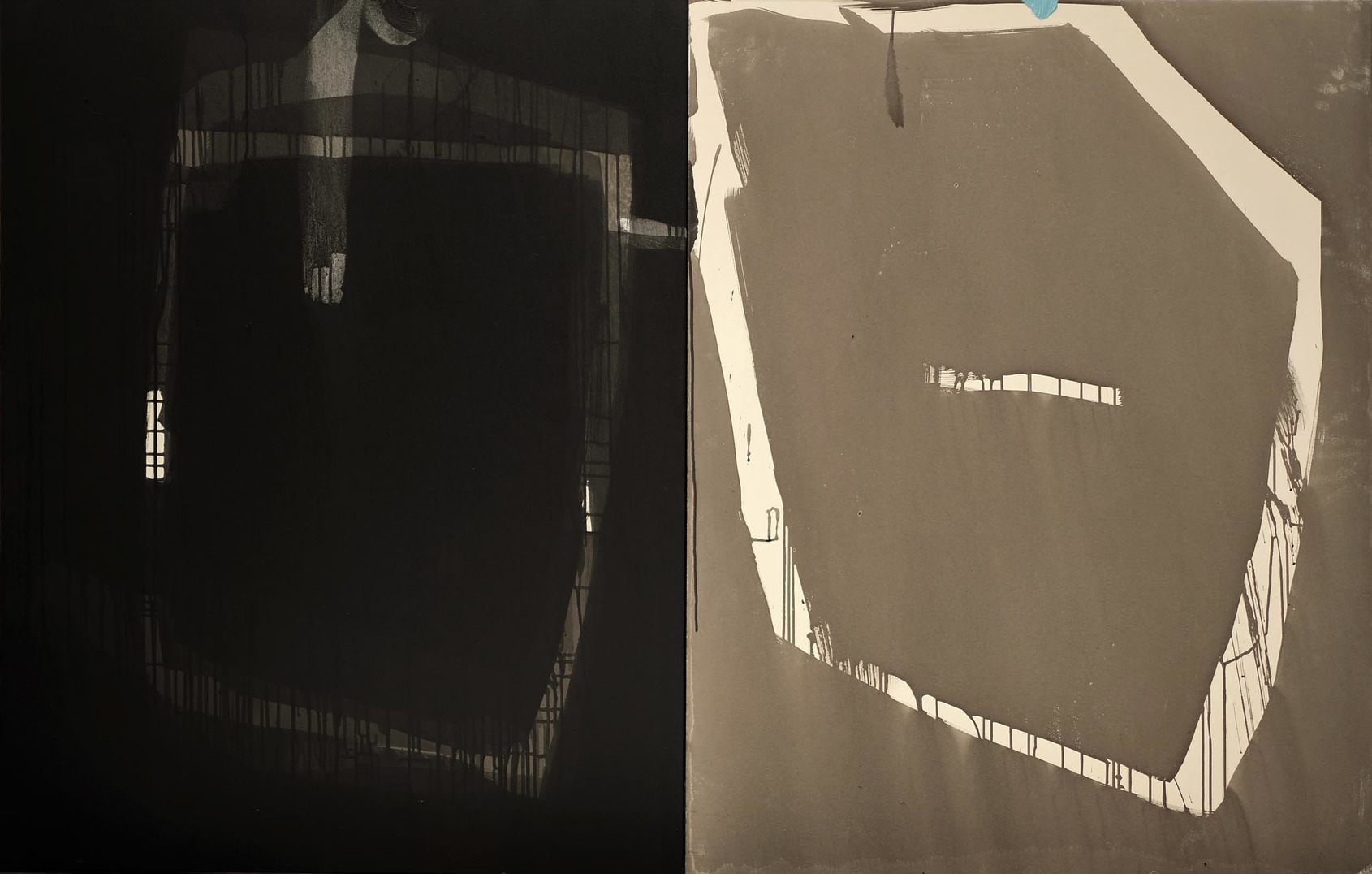

Lin Hong-Wen, Untitled 11, 2019, acrylic color, canvas, 60 x 72 cm There is little doubt that Hong-wen’s paintings require a sense of time to see accurately. In fact, they require both time and reflection. The contemplation of the spatial intervals in his work, whether in two or three dimensions is essential to the work. As I focus on Untitled 11 and Untitled 6 (both 2019), I become aware that Untitled 11 is painted on a single canvas. Therefore, the complexity is reduced. The surface is relatively self-contained and relatively easy to decipher on a formal level. In Untitled 11, one might detect at least five, possibly six, layers of thinly applied paint. It is important that the drips remain rather than painted over. The spatial intervals are created one at a time with intermittent pauses. The surface gradually defines itself through the artist’s use of transparency and lateral construction. Untitled 11 should not be misunderstood as a predetermined composition (in Western terms). Rather it is a painting that has evolved over time into what the artist believed it should become.

In contrast, the two-paneled Untitled 6 purposely demarcates between white and black panels that ultimately give the painting its unusual significance. The balance is present, but so is the counter-balance, which ultimately seems to disappear. Rather a somewhat odd intrusion occurs within the space revealing two intuitive marks that ignite the surface in such a way to give the painting a distinct, if not obverse, thoroughly humorous neutrality.

Lin Hong-Wen, Untitled 6, 2019, acrylic color, canvas, 182 x 91 cm Even so, I am struck by the incestuous meandering of Hong-wen’s painterly diptychs for the reason that the differences on either side of these two-paneled paintings are interrelated in abstract terms. As an artist, he returns the function of the diptych to its original meaning wherein each panel has a complementary relationship to the other. Rather than one panel negating the content of the other in abstract terms, Hong-wen’s diptychs reveal an omniscient simultaneity in which each panel foregoes opposition. In this sense, the diptych is paradoxically unified. The two parts of the painting come together despite radical differences.

In contrast, Hong-wen’s welded steel sculptures leave little doubt of their being in the three-dimensional present. There is a sense of immediacy in each of the four Steel Sculptures (2019). The tactile feeling of the steel surfaces is direct, as it would be in bronze. But it is not bronze, it’s steel! And steel has its own texture, its own tactile definition. Each of the four versions has a difference, whether through angle or curve. The welded creases are overtly placed equidistantly between the various planes as they ascend upwards. Whether sculpture or painting, each medium expresses its own sense of tactility in different ways. The formation and discipline of the vertical steel elements in the Sculptures can be seen from various angles in relation to the environment in which they are placed or in relation to one another.

Lin Hong-Wen, Untitled 4, 2019, steel, 113 x 29 x 202 cmLin Hong-Wen, Untitled 1, 2019, steel, 45 x 38 x 206 cm In fact, the acute elements in the sculpture complement the paintings, given the alternative drips and slashes and their subtle open-ended forms. Whereas the steel is unified with one element adjacent to another, Hong-wen’s painterly surface effects are seen differently. Whether on a single surface or presented as a diptych, the paintings have their own tactile or haptic sensation, a sensory light that touches the retina of the eye.

Where is the place on the canvas where light is admitted? No matter how hidden the light may appear, around or beneath the artist’s thinly painted dark veils, there is the sense of touch. Given the current environment where the human touch is necessarily forbidden, there is no doubt that art of this quality can help restore the memory of touch. Artists the caliber of Lin Hong-wen are healers – as many significant artists tend to be – whose work may help show us the way through their knowledge of rehabilitation as art restores our ability to think again in terms our human condition.

I would like to take this opportunity to offer my deepest thanks to the artist, Lin Hong-wen, and to the curator of this exhibition, Dr. Yaman Shao. Their encouragement and friendship has been and continues to be overwhelming. Their appreciation and trust in my work as a writer on Chinese and Taiwanese contemporary art reveals a generosity of spirit that I have grown to understand as an essential part of a great culture.

Note on the Curator

Robert C. Morgan is a writer, critic, curator, artist, and art historian, who is the author of many books and monographs, including Art into Ideas: essays on Conceptual Art (1996,Korean translation,2007) The End of the art work(1998) and Vasarely (2004). He has authored catalogs on Chinese artists, including Zeng Fanzhi, Ye Yongqing, Cui Guotai, Wenda Gu and Zhang Jian Jun, and is the New York Editor of Asian Art News. Dr. Morgan has curated over 70 exhibitions in museums, galleries, and cultural spaces throughout the world, including the first New York exhibition of Hung Liu in 1989. His own work as an artist is represented by Bjorn Ressle Gallery in New York. NEW YORK, NY, July 17, 2019 /24-7PressRelease/ -- Marquis Who's Who, the world's premier publisher of biographical profiles, is proud to present Robert C. Morgan, PhD, with the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award. An accomplished listee, Dr. Morgan celebrates many years' experience as a professional advocate in the field of contemporary art. He is noted for his scholarly and educational achievements in studio art, art criticism, the history of art, and his curatorial practice.